Trauma can have profound and lasting effects on children’s neurological, emotional, and social development. For educators, understanding these impacts is vital for creating environments where children feel safe, seen, and supported. Let’s explore the ways trauma affects young brains and practical strategies educators can use to help children thrive.

Understanding Trauma and Its Long-Term Effects

What Is Trauma?

Trauma is a deeply distressing or disturbing experience, often leaving a lasting imprint on mental and physical health. For children, traumatic experiences—such as abuse, neglect, or the loss of a loved one—can overwhelm their ability to cope, especially when they lack a supportive environment.

The effects of trauma in childhood can be staggering. Research shows that children who experience trauma are twice as likely to develop depression and three times as likely to suffer from an anxiety disorder in adulthood. The implications of trauma can ripple across their perception of safety, ability to form relationships, and behaviour, often wiring their brains to expect danger and triggering heightened stress responses.

Types of Trauma in Childhood

Trauma manifests in different forms, and each type can have unique impacts:

- Single-Incident Trauma: This occurs after a one-time, unexpected event, like a car accident or natural disaster. While significant, these events are usually easier to process with timely support.

- Complex Trauma: Repeated exposure to harmful interpersonal events, such as abuse or neglect, falls under this category. It often results in more severe and lasting effects on brain development and emotional regulation.

- Historical Trauma: Multigenerational trauma experienced by cultural groups, such as the impact of colonisation on Indigenous communities, affects not only individuals but entire families and societies.

- Intergenerational Trauma: Trauma passed down from one generation to the next, often through patterns of parenting and behaviour influenced by unresolved trauma in caregivers.

The Neurological Impact of Trauma: How Trauma Alters the Brain

The brain undergoes rapid development in the early years of life, making it highly vulnerable to the effects of trauma. Key brain regions affected include:

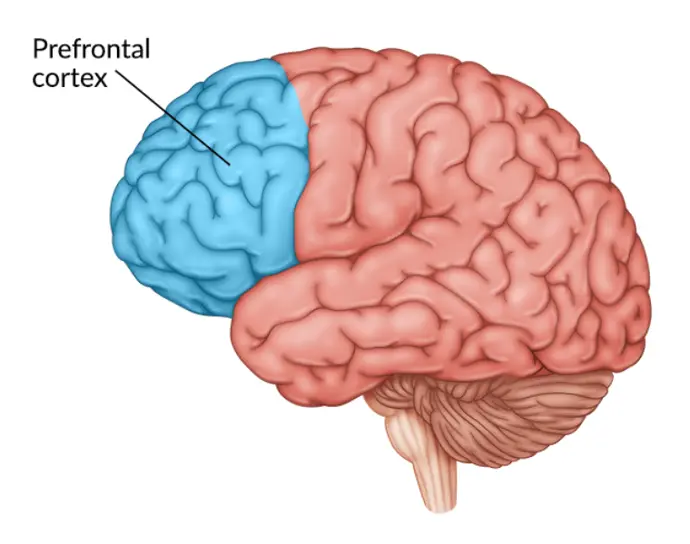

Prefrontal Cortex

Responsible for problem-solving and reasoning, this area often shows reduced grey matter volume in trauma-affected children, impairing their decision-making and impulse control.

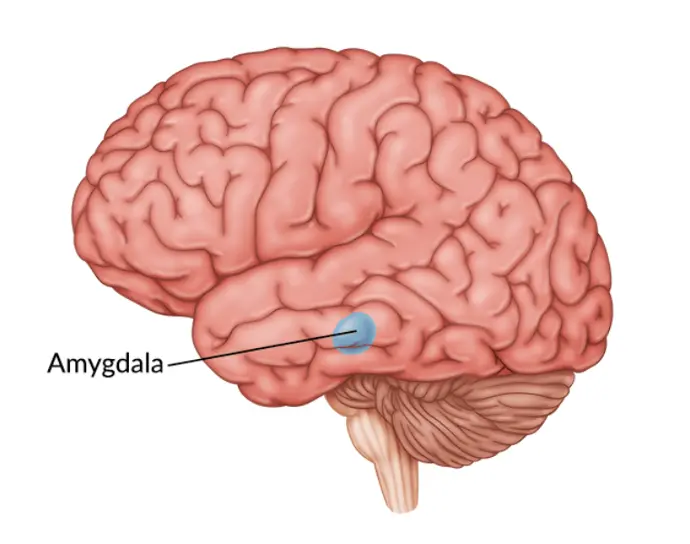

Amygdala

Known as the brain's fear centre, the amygdala becomes hyperactive in children with trauma, leading to heightened fear responses and difficulty regulating emotions.

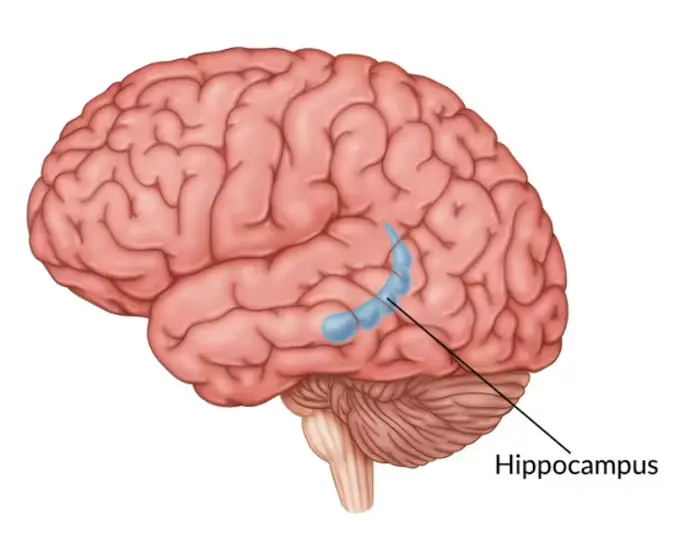

Hippocampus

Crucial for memory and learning, the hippocampus often shrinks in trauma-affected children, making it harder for them to process and retain new information.

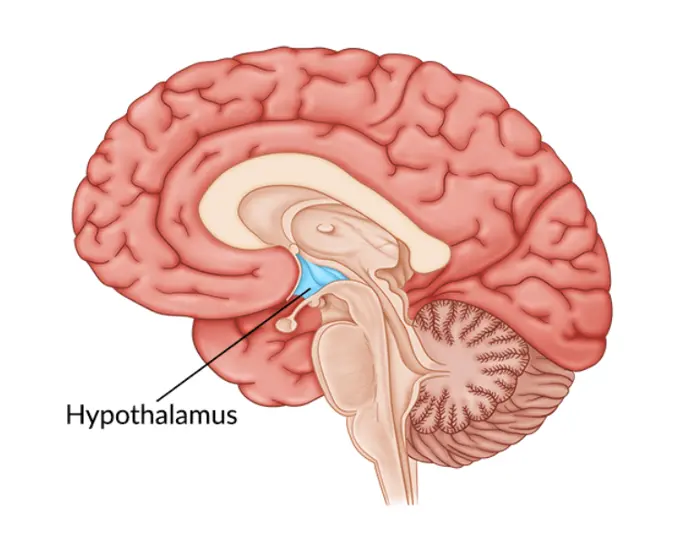

Hypothalamus and the HPA Axis

Trauma disrupts the body's stress regulation system, leading to hormonal imbalances that can cause sleep disturbances, hypervigilance, and difficulty managing anxiety.

These neurological changes can result in behavioural patterns such as withdrawal, aggression, hyperactivity, or emotional numbness. Children may struggle with relationships, concentration, and academic performance, often feeling unsafe or unable to trust others.

Neuroplasticity and the Hope it Offers

While the effects of trauma can be significant, the brain’s incredible ability to heal, known as neuroplasticity, offers hope. Especially in young children, the brain can rewire itself through supportive relationships, consistent routines, and nurturing environments. For example, children who lose speech due to early trauma can often regain this ability over time with the right interventions. Neuroplasticity demonstrates that a traumatised brain is not broken or damaged, instead it is adaptable and wired for survival.

Creating a Trauma-Sensitive Learning Environment

Educators play a crucial role in fostering resilience, wellbeing, connections and safety in children who have experienced trauma. Here are some strategies to create an environment that is trauma-sensitive and supportive for all children.

- Understand the Child: Recognise that children affected by trauma may behave or react in ways that seem disproportionate. They may be developmentally younger than their peers in emotional regulation or social skills. Approach them with empathy and curiosity, not judgement.

- Prioritise s sense of security: Children exposed to trauma often feel a lack of control in their lives. Establishing a sense of predictability and known outcomes can help them feel safe. However, remember that predictability does not mean rigidity. It is about creating a sense of stability.

- Use “Time-In” Instead of “Time-Out:” Traditional behaviour management methods such as positive and negative reinforcement such as giving our connection (or 'attention') to behaviours we see as positive and removing it for behaviours we see as negative, can inadvertently reinforce feelings of rejection. Instead, “time-in” strategies where the adult stays present and engages with the child, help build trust and reduce shame.

- Manage Your Own Reactions: Children are highly attuned to the emotional states of adults. Staying calm in the face of behaviours supports co-regulation, helps de-escalate hyperarousal states in children and models emotional regulation strategies.

- Empower, Don’t Overpower: Trauma can leave children feeling powerless. By offering choices and involving them in decision-making, educators can help rebuild their sense of agency, trust and connectedness.

Relationships and Connections

Observation and connection are key when supporting children exposed to trauma. Children in a state of hyperarousal (e.g., aggressive or reactive behaviour) or hypoarousal (e.g., withdrawal or disengagement) need adults who can "tune in" to their emotional states and respond with sensitivity.

Trauma often diminishes a child’s sense of connection and safety. By creating an environment that feels secure and relational, educators can fill these critical needs. Simple gestures like offering a calm tone of voice, providing physical comfort when appropriate, and showing consistent responses and level of care can make a world of difference.

Children affected by trauma often face barriers to learning, such as:

- Reduced Cognitive Capacity: Tasks may feel overwhelming, leading to frustration or avoidance.

- Sleep Disturbances: Poor sleep can impact concentration and mood, further hindering the ability to focus.

- Memory Difficulties: Trauma can impair memory retention, making it harder for children to follow instructions or recall information.

- Language Delays: These may affect their ability to communicate effectively or understand explicit instructions.

As early years educators then, we can employ strategies to support children's learning, engagement and wellbeing in our programming and planning. These include:

- Breaking tasks into smaller steps. When we simplify instructions, it can make tasks feel more manageable.

- Planning for the creation of calm learning environments. Minimisation of sensory overload can help children to feel secure and more effectively regulate their emotions.

- Celebrate with children. Engage as co-constructors in learning and play. Celebrate children's successes - no matter how small!

- Plan for movement. Physical activities can help regulate emotions and improve focus. See our blog exploring the power of physical activity in supporting children to heal through trauma (Link to Blog on trauma and physical activity).

- Stop the rushing. Allow children to take their time without pressure and explore their world at their own pace. There is no need to rush, yet as adults we often feel the pressure of time. Remember that children are often blissfully unaware of time pressures.

Understanding the neurological and behavioural impacts of trauma allows educators to approach children with greater compassion and effectiveness. By creating safe, predictable environments and using trauma-informed strategies, we can help children not only recover but thrive.

Trauma doesn’t define a child’s future. With support, patience, and empathy, we can be part of the healing process that enables children to embrace their own identity and individuality. Every small step we take in understanding and supporting these children builds a foundation for resilience, growth, and hope.

Want More On Trauma Informed Practice?

Check out our program, Safe, Seen & Supported! Available as an in service workshop or an online course, it is full of practical strategies and quality content.