Before I answer the question posed in the title of this blog, let’s remind ourselves of the purposes of group story and song sessions in early childhood settings.

Purposes of group story and song sessions:

Reading aloud and singing with children is an important part of any early literacy program. Reading books together gives children tremendous insight into the act of reading long before they even begin to decode words on a page for themself. In addition, reading together serves to:i

Reading aloud and singing with children is an important part of any early literacy program. Reading books together gives children tremendous insight into the act of reading long before they even begin to decode words on a page for themself. In addition, reading together serves to:i

- excite children about learning

- give children opportunities for language enrichment

- help children make sense of story sequences

- satisfy children’s need for closeness and communication

- teach turn taking, leadership and following.

However, all this is hard to achieve in large groups, partly because of the nature of young children, and partly because of the nature of large groups.

Nature of young children

To understand what makes group time so difficult for children, we need to remember what we know about child development. Four characteristics are relevant here: children’s natural group size, their attention span, their language development, and their learning style.

Natural group size

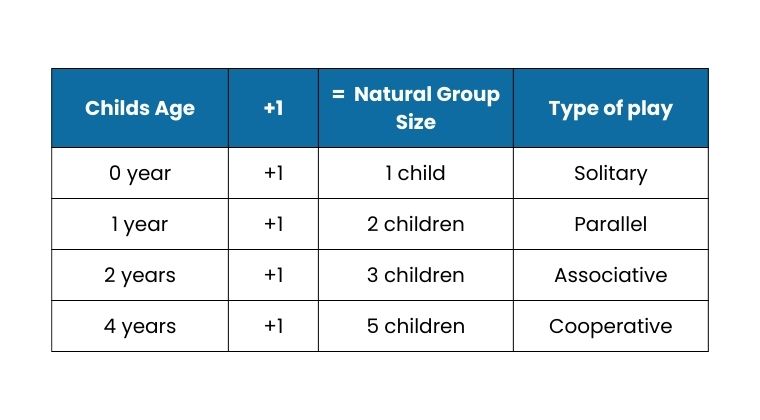

In terms of group size, we know that young children naturally gather in groups where the number of children is one more than their age:ii

This natural group size tells us that, even when the setting is big enough to accommodate a large group, the children themselves can find it difficult to cope in a crowd, particularly when the task is demanding – such as during group story time, when their language, concentration and sensory integration skills may all be simultaneously challenged.

Concentration span

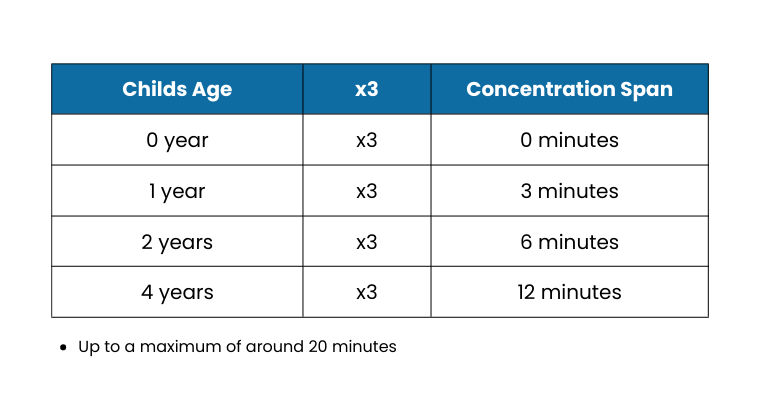

As for concentration span, I’ve always thought of children’s attention span for adult-led activities as being around three minutes multiplied by their age in years (up to a probable maximum of around 20 minutes). When you are fascinating, passionate and engaging, you can double this for around 80 per cent of children. However, you cannot double it for every child – and you cannot triple it for anyone, because concentrating for prolonged periods depletes children’s energy and, with it, their ability to focus.iii

Language skills

Children learn language within their relationships. Their language abilities are directly related to how much time they spend talking with and listening to adults.iv

Children can experience a rate of words per hour at home ranging from 616 through to 2153 words per hour, depending on the socioeconomic*** conditions in which they are living. This equates to between 3 million (at the lower end of the scale), and 11 million words (for more advantaged children) across a year.

This means that children who are experiencing complex adversities at home, and therefore are at the lower end of the range, are most in need of one-on-one or small group interactions in their care and education settings to provide the language stimulation that they might not be receiving at home.

*** "Socioeconomic status is the position of an individual or group on the socioeconomic scale, which is determined by a combination of social and economic factors such as income, amount and kind of education, type and prestige of occupation, place of residence, and—in some societies or parts of society—ethnic origin or religious background.

Examinations of socioeconomic status often reveal inequities in access to resources, as well as issues related to privilege, power, and control."

Adapted from the APA Dictionary of Psychology as cited on the American Psychological Association website.

Large group settings do not readily match children's capacity to engage in them.

Large group settings do not readily match children's capacity to engage in them.

Children’s learning style

Babies and young children are natural scientists.vi They are always observing and experimenting, and are seldom idle. Holt observes that their activities are purposeful and intense as they soak up their experiences and try to make sense of their world, to figure out how things behave.

Play is the vehicle by which children construct knowledge about the world, and acquire and consolidate their skills.vii Seen in all mammals, it is children’s primary way of making sense of their world.viii It is not children’s ‘work’ so much as a way of using the mindix that allows children to experience being in their element.x Another term for this experience is ‘flow’ – which is when our energies (or attention) are focused on achievable and meaningful goals that are under our control.xi

Movement and doing, then, are how children learn. As Dowling observes: ‘The most demanding level of movement for a child is to stay still’.xii Of course, group times require that they do exactly this.

Disadvantages of large group settings

Many of these natural characteristics of children suggest that large group sessions do not readily match children’s capacity to engage in them. Specifically, research tells us that compulsory group story and song sessions (or ‘circle time’) present many difficulties.

Self-efficacy

The first disadvantage is that these sessions are often mandatory. This deprives children of choice. However, I believe that the main goal of early childhood education is to teach children what is known as self-efficacy. This is the belief that we can make things happen in our lives, that we are effective at running our lives. In education, specifically it refers to teaching children that they can make learning happen for themselves: that they are effective learners.

Picture the child, then, who is busy trying to understand weights and measures (otherwise known as ‘playing in the sandpit’) who is testing what works and doesn’t (otherwise known as being a scientist) and is forced to come away from that experiment to listen to a story that has nothing to do with science. If we want children to have self-efficacy, we must allow them to see through what they are doing to its natural conclusion. Given that we can’t read minds, we have to assume that they are doing and thinking about something valuable – something, therefore, that should not be interrupted.

Behavioural challenges

If group sessions are compulsory, children who prefer not to participate are likely to disrupt others by being restless or by attempting to escape. This means that we have to have a second adult up the back of the group making children stay there (the educator whom I call the ‘boundary rider’).

Meanwhile, large group sessions commonly over-extend children’s concentration span. Disruptions from disengaged children become more likely the longer session continues.xiii

And we have to time the session from when the first child goes to the mat: Sometimes, it can be 10 or 15 minutes before the session actually starts, which means that this child’s concentration span has been exhausted or (worse still to my mind) that this child has been taught to be such a compliant, passive learner that he or she no longer even protests.

Large group sessions commonly over-extend children’s concentration span.

Large group sessions commonly over-extend children’s concentration span. Children with learning difficulties

Children with language difficulties, limited concentration span, or sensory integration difficulties can find it impossible to learn within the large group setting. Sometimes, I see these children being allowed to ‘vote out’ of the session – that is, to choose not to come. However, this makes an exception of a child whose developmental profile already puts him or her at risk of being ignored. It implies to the other children that it’s okay not to expect this child to participate in their play.

As for children with delays and disabilities, they tend to be only passively engaged during group times, in which case they will be learning little. In contrast, they are more likely to be actively engaged and to interact with their peers during free play.xiv .

Emotional needs for connections

When conducting large groups, it is impossible to satisfy children’s emotional needs for closeness and intimacy.xv Children’s social acceptance and friendships are a major source of their pleasure in their educational settings.xvi And, although in early childhood they get more contact with peers than further up the schooling system, group times are intended to be social. Yet for the most part the children cannot interact with each other. Their drive to do so is why the children at the back are chatting to each other, despite constant reminders to listen to the educator.

Language skills

The main purpose of group sessions is language stimulation. However, the nature of large groups means that they fail spectacularly at this. Few children can get to talk within a large group. Even if everyone had equal turns, it is not possible for young children (or anyone of any age) to wait for 19 others to have their say before contributing to the conversation. By then, what we wanted to say would be off-topic. And none of us could have a dinner party with 20 guests where only one conversation was happening and we had to wait to have our say until the person to our left had theirs. No one – not even adults – can wait that long. Instead, at a dinner party we would break up into smaller groups of three or four, and have separate conversations. No wonder this is what happens during large group sessions with children.

Especially when children’s home environment might not be supporting optimal language development, educators’ conversational responsiveness is vital. This means responding to what our communication partner says, and maintaining topics over successive turns.xvii Children need both a high quantity of interactions (frequent conversations comprising four or more turns each by the adult and child) and high-quality (responsive) interactions to advance in their language skills. This can’t be done in large group settings.

Children’s responses to group times

As if the above disadvantages are not enough, research tells us that being deprived of choice and having limited opportunity for true interaction causes children to dislike large group sessions and to regard them as ‘work’.xviii The result is that, although the sessions could be teaching valuable information, they might also be teaching children that learning activities are dull. This is the last thing we want.

Educators' responses to group time

And what about the educators? Having to run sessions with constant interruptions and disruptions is downright hard work. Doing so typically involves enormous numbers of corrective and directive statements from educators to keep individual children engaged. But, as Gottman’s ratio tells us, for every one of these negative instructions, we need to give children five positive comments. But there is no time to offset the negative tone of all those corrective statements. This is not good for children’s emotional wellbeing… and educators do not want to be instructing children like this.

Luckily, there is an alternative. We can give ourselves a break – and be more effective at the same time.

The alternative

In my observations of large group sessions, I am struck by the one-third ratio: One third of the children are engaged for the most part. They are sitting up the front and joining in. One third of the children are engaged now and then and, during down times, are ‘day dreaming’ but not actively disrupting the session. And the remaining one third of the children are rolling around in the back rows, calling out now and then when something finally interests them but, on the whole, spend the time chatting to and poking the children nearby.

Other than the one-third who are engaged, what is group time teaching the remaining two-thirds? And if only one third is engaged, why not run a group time for just those children?

One simple solution, therefore, is to make group time voluntary. Instead of conducting whole-group sessions, we would offer a series of small-group interactive experiences throughout the day.

These sessions would look like this: An educator could sit outside and begin to play a musical instrument, or could approach one or two children who were not deeply engrossed in play and would ask if they would like a story. Once captivated, others might choose to join the group also. Sometimes, everyone would elect to participate but, if the group became too large, some might decide to wait until the next session. And for those attending, once their concentration had waned, they could leave.

A variant on this is to conduct ‘workshops’ that children can choose to attend but, once there, stay until the session ends.xix Children can come up with their own ideas for the topics of these workshops.xx

These sessions would occur three or four times a day, with leaders noting on a card who attended. Over the course of a week, you would find that most children would be participating. Although children who attended the centre daily might participate in only three sessions over the course of a week (instead of daily compulsory sessions), those interactions would be more enriching and relevant for them and therefore they would potentially learn more.

Sometimes, what you offer will be so inviting that all the children choose to come. This ‘voting in’ is very different from making an exception of a few children, though. It avoids stigmatising the few ‘exceptional’ children, and still engages the children in actively choosing to manage their engagement themselves.

For the few children who do not choose to attend, you could conduct one-on-one sessions in an effort to understand the reasons they are not participating. You might look out specifically for whether:

- the language is either too simple for gifted learners, or too advanced for those with language impairments or for whom English is their second or third language

- the children have concentration difficulties

- they have sensory integration problems that make them uncomfortable in group settings where they might get jostled or touched unexpectedly

- they lack social motivation, as seen in children on the autism spectrum.

If your observations of these children then suggest a developmental concern, you would recommend that their parents obtain an assessment to guide you in how best to support their learning.

Benefits of voluntary group time

Conducting voluntary group times as described above will:

- prevent behavioural difficulties in those children who are reluctant to attend or who find the content or process of large sessions difficult

- respect children’s play (otherwise known as self-directed learning) by avoiding interrupting it

- avoid teaching children that language-based activities are ‘boring’

- prevent those who assemble early having to wait while others arrive

- honour children’s capacities by limiting the number of people in the group, thereby keeping the group size manageable for the children

- enrich children’s language experience in the smaller grouping

- allow the children to leave once their attention disappears, resulting in fewer behavioural disruptions

- satisfy their needs for close connections

- give the children choice and increase their confidence in making choicesxxi

- give children experience of regulating their own attention, impulses and emotions.

Voluntary sessions do pose scheduling challenges, which your team would need to plan for.

Preventing those who assemble early having to wait while others arrive

Preventing those who assemble early having to wait while others arrive

What about school readiness?

Some say that we have to insist on compulsory group times to prepare children for school. However, when children choose to attend, they are choosing to regulate their attention, emotions and impulses – and this skill (not the ability to sit passively in groups) will be the most vital for their achievement at school.

Indeed this type of intellectual maturity in general and self-management skills in particular play a central role in children’s readiness for and success at school,xxii accounting for 25 per cent of their adjustment and success in the early years of school.xxiii Their learning processes are more important than specific literacy and numeracy skills such as knowing the alphabet or being able to count.xxiv

Some say that we have to insist on compulsory group times to prepare children for school. However, when children choose to attend, they are choosing to regulate their attention, emotions and impulses – and this skill (not the ability to sit passively in groups) will be the most vital for their achievement at school.

Indeed this type of intellectual maturity in general and self-management skills in particular play a central role in children’s readiness for and success at school,xxii accounting for 25 per cent of their adjustment and success in the early years of school.xxiii Their learning processes are more important than specific literacy and numeracy skills such as knowing the alphabet or being able to count.xxiv

Success at making the transition to school also depends on children’s social and behavioural competencies.xxv These account for around 10 per cent of children’s reading and maths progress in the early school years.xxvi Children with poor learning-related skills begin school performing below their peers and continue to lag three years later.xxvii

Children’s ability to regulate their emotions directly affects their success and productivity at school.xxviii This ability may be particularly crucial for navigating school entry, because the new learning environment and challenging academic tasks can arouse anxiety and frustration, which must be managed. In turn, teachers view well-regulated children more positively, which contributes to an improved teacher-child relationship that, in turn, also supports children’s educational engagement and attainment.xxix

In other words, self-regulation (rather than being controlled by a ‘boundary rider’) is the most vital skill for a successful transition to school and for success once there.

Even if this were not true, just because particular behaviours such as sitting in a large group might be achievable by school-aged children, this does not mean that they are achievable – or even beneficial – at younger ages. What’s more, most children will mature into school routines as they near the school starting age, but this is no more – and perhaps even less – likely if we force them to do so before they are capable.

Conclusion

We can meet our goals for children’s learning at the same time as respecting their capacities when we offer activities and make resources available to them that are in tune with the natural rhythm of their day and which honour their learning through play, rather than interrupting it for compulsory group times. For children to learn, they need to be able to trust that the world is predictable and they need to be able to trust themselves. Our job, then, is to put ourselves into contact with the intelligence of children,xxx so that they have the space and time to fall in love with what they are doing.

Download this Article

Please subscribe below to download a printable copy of this article:

References

Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., McGinty, A. S., DeCoster, J., & Forston, L. D. (2015). Teacher-child conversations in preschool classrooms: Contributions to children’s vocabulary development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 30(1), 80-92.

Conlon, A. (1992). Giving Mrs Jones a hand: Making group storytime more pleasurable and meaningful for young children. Young Children, 47(3), 14-18.

Cook, P. & teachers from the Early Assistance Action Research Project in South Australia. (2008). Whose language is group time anyway? In G. MacNaughton, P. Hughes, & K. Smith (Eds.), Young children as active citizens: Principles, policies and pedagogies (pp. 193-209). Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Csikszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial.

Davidson, A. J., Gest, S. D., & Welsh, J. A. (2010). Relatedness with teachers and peers during early adolescence: An integrated variable-oriented and person-oriented approach. Journal of School Psychology, 48(6), 483-510.

Dowling, M. (2005). Young children's personal, social and emotional development. (2nd ed.) London: Paul Chapman.

Ebbeck, M., Yim, H. Y. B., & Lee, L. W. M. (2013). Play-based learning. In D. Pendergast & S. Garvis (Eds.), Teaching early years: Curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (pp. 185-200). Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Fields, M., & Boesser, C. (2002). Constructive guidance and discipline. (3rd ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Gestwicki, C. (2014). Developmentally appropriate practice: Curriculum and development in early education. (5th ed.) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Graziano, P. A., Reavis, R. D., Keane, S. P., & Calkins, S. D. (2007). The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology, 45(1), 3-19.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Eyer, D. (2003). Einstein never used flash cards. New York: Rodale.

Holt, J. (1982). How children fail. (rev. ed.) New York: Merloyd Lawrence.

Jung, J., & Recchia, S. (2013). Scaffolding infants’ play through empowering and individualizing teaching practices. Early Education and Development, 24(6), 829-850.

Justice, L. M., McGinty, A. S., Zucker, T., Cabell, S. Q., & Piasta, S. B. (2013). Bi-directional dynamics underlie the complexity of talk in teacher-child play-based conversations serving at-risk pupils. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(3), 496-508.

Kemp, C., Kishida, Y., Carter, M., & Sweller, N. (2013). The effect of activity type on the engagement and interaction of young children with disabilities in inclusive childcare settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(1), 134-143.

La Paro, K. M., & Pianta, R. C. (2000). Predicting children’s competence in the early school years: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 70(4), 443-484.

Ladd, G. W., Birch, S. H., & Buhs, E. S. (1999). Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development, 70(6), 1373-1400.

McClelland, M. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2003). The emergence of learning-related social skills in preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 18(2), 206-224.

McClelland, M. M., Morrison, F. J., & Holmes, D. L. (2000). Children at risk for early academic problems: The role of learning-related social skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(3), 307-329.

McWayne, C. M., Fantuzzo, J. W., & McDermott, P. A. (2004). Preschool competency in context: An investigation of the unique contribution of child competences to early academic success. Developmental Psychology, 40 4), 633-645.

Miles, S. B., & Stipek, D. (2006). Contemporaneous and longitudinal associations between social behavior and literacy achievement in a sample of low-income elementary school children. Child Development, 77(1), 103-117.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2003). Social functioning in first grade: Associations with earlier home and child care predictors and with current classroom experiences. Child Development, 74(6), 1639-1662.

Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., Cabell, S. Q., Wiggins, A. K., Turnbull, K. P., & Curenton, S. M. (2012). Impact of professional development on preschool teachers’ conversational responsivity and children’s linguistic productivity and complexity. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(3), 387-400.

Piotrkowski, C., Botsko, M., & Matthews, E. (2000). Parents’ and teachers’ beliefs about children’s school readiness in a high-need community. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(4), 537-558.

Porter, L. (1999). Behaviour management practices in child care centres. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Adelaide: University of South Australia.

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2009). The element: How finding your passion changes everything. New York: Penguin.

Shanker, S. (2013). Calm, alert, and learning: Classroom strategies for self-regulation. Don Mills, ON: Pearson.

Turnbull, K. P., Anthony, A. B., Justice, L., & Bowles, R. (2009). Preschoolers’ exposure to language stimulation in classroom serving at-risk children: The contribution of group size and activity context. Early Education and Development, 20(1), 53-79.

Wiltz, N. W., & Klein, E. L. (2001). ‘What do you do in child care?’: Children’s perceptions of high and low quality classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 16(2), 209-236.