Psychology: The science of behaviour (Carlson & Buskist, 1996) was the first textbook I owned as a bright-eyed undergraduate embarking on my mission to leave the world just a little bit better. It was printed in 1997, and so did not have a whisper of the yet to be acclaimed Positive Psychology movement. When I brush the dust off to open this book, which still has pride of place on my bookshelf, I flick through noticing the pages outlining the pathologising and negative focus that was to be my degree. One thing that stands out for me, is the thirty-four consecutive pages dedicated to the science of behaviourism, illustrated by figures of lab studies with a menagerie of animals from Pavlov’s dogs, through to rats in a chamber, and pigeons in a box. A couple of hundred pages later, the reader is introduced to humanistic psychology across four short pages, one of those concluding that “although the humanistic approach emphasizes the positive dimensions of human experience, and the potential that each of us has for personal growth, it has been faulted for being unscientific. Critics argue that its concepts are vague and untestable.” (Carlson & Buskist, 1996, p. 475)

From my initial introduction into the world of psychology being behaviourism, it is little wonder that for the first few years of my work with children and complex behaviour, I leaned on the ‘evidence’ from the likes of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), operant conditioning, and behaviour modification methods defined by behaviourists. Fortunately, by the time I moved on to working with teachers and educators, supporting them to find evidence-based practices to guide children’s behaviour, Positive Psychology had gained traction. The reason for its existence; to guide a redirecting of scientific energy to measure, understand, and build those characteristics that make life most worth living (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Positive Psychology’s application to the everyday classroom is yet to be seen on a large scale, nevertheless, we are on the verge of seeing this movement spill into schools and early childhood settings. This will have an enormous impact on the flourishing of children and in turn, humanity.

At the turn of the new century, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) marked the turning over of a new leaf for the field of psychology, with their paper introducing a framework for a science of Positive Psychology. They boldly predicted the rise of a psychology of positive human functioning that will bring with it a scientific understanding and interventions with a focus on flourishing from individuals to whole communities. The authors claim that “psychologists have scant knowledge of what makes life worth living” (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 5), as they have come to focus exclusively on pathology. In this introduction to a dedicated edition of American Psychologist, they paint a picture of chaos and despair should Americans “continue to increase its material wealth while ignoring the human needs of its people and those of the rest of the planet” (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 5).

I have personally been fuelled by this call to action, to advocate for the human needs of our youngest citizens. In my work as a consultant, often called upon when adults are in crisis about children’s behaviour, I have noticed that these behaviours are children’s attempt to communicate their unmet needs – their wellbeing. Children who are communicating their illbeing through behaviours that adults deem disruptive are not something to be managed, shaped, modified, rewarded, or positively reinforced. We must interpret the behaviour, draw on frameworks, theories, and research to guide our decisions about how to respond in a way that fosters wellbeing, and does not contribute to illbeing.

Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi’s founding paper in the year 2000 pointed out large gaps in our knowledge, and directions for further research. The authors name-drop the philosophical works of the likes of Democritus, Epictetus, and Camus, to name a few, and pay homage to the work of humanists ever since. However, as we see very little of such philosophy applied to pedagogy in the modern classroom, we would see the same of Positive Psychology for some time. As inspiring as this announcement of a movement was, it gave few clues about what practices to apply in our work with children, and so, it is still a rare classroom or early learning environment where will see the echoes of Positive Psychology in action.

Just under a decade later, a new term was coined by Seligman, Gillham, Reivich, and Linkins (2009); Positive Education. Their paper Positive Education: positive psychology and classroom interventions, asks us to imagine a world where schools teach both the skills of wellbeing and the skills of achievement without compromising the other. They cite the necessity for this by preceding their argument that depression is more common now than it was fifty years ago, despite the fact that almost everything is better now than it was then (Seligman et al., 2009). Perhaps even more convincingly, the authors argue the reason for teaching wellbeing to children is that “more wellbeing is synergistic with better learning” (Seligman et al., 2009, p. 294). After concluding that wellbeing should be taught in schools, given their untapped potential for such initiatives, the authors also argue that indeed, wellbeing can be taught in schools.

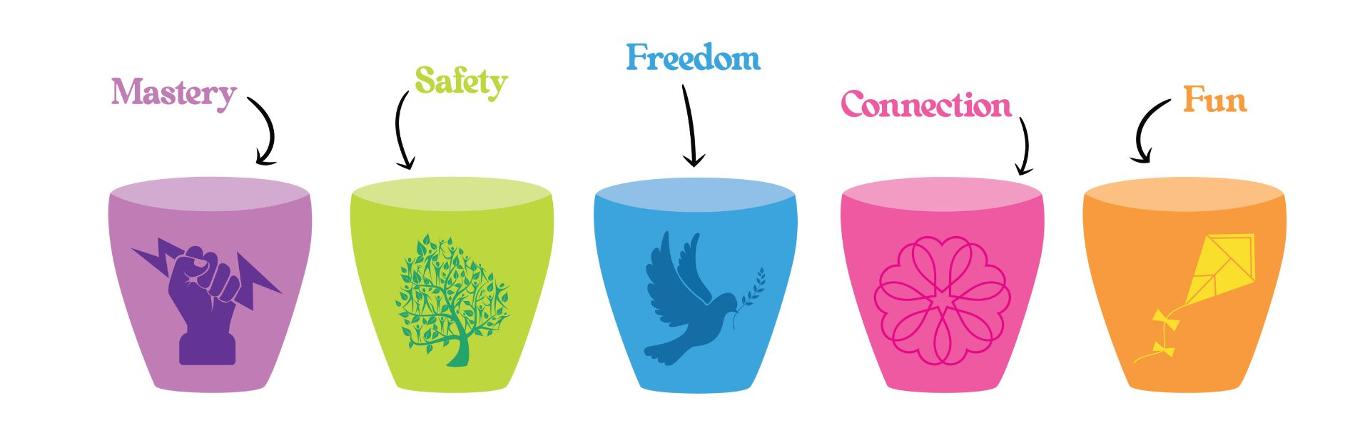

Yet still, we wait for traditional ways of classroom management and teaching to grow into ways that support flourishing. A potential barrier to this is that despite the increased interest in school wellbeing, the field is lacking conceptual clarity and useable frameworks (Waters & Loton, 2019). I believe what we need to see this movement gain traction across Australia are strong foundations and frameworks that will guide programmes, interventions, teachers and educators to successfully apply humanistic psychology, the guidance approach, Positive Psychology, and Positive Education. The Phoenix Cups® framework (Phoenix & Phoenix, 2019) answers this call. With an easy to learn common language, and relevant educator training, this framework allows contemporary psychological ideas and research to be quickly conveyed, considered, and applied in education and care contexts. The Phoenix Cups represents needs as Cups and provides a framework for educators, teachers, and parents, to understand children’s behaviour as their best attempt to meet their need, or fill their Cups. The framework asks adults to imagine each child (and indeed humans, regardless of age) having the ‘Will to Fill’™ five different Cups; Their Safety Cup® (to achieve security), their Connection Cup® (to achieve self-worth), their Freedom Cup® (to achieve autonomy), their Mastery Cup® (to achieve self-competence) and their Fun cup® (to achieve joy).

These five Cups are symbolised by five distinct icons and colours to help adults remember each of these important basic human life needs.

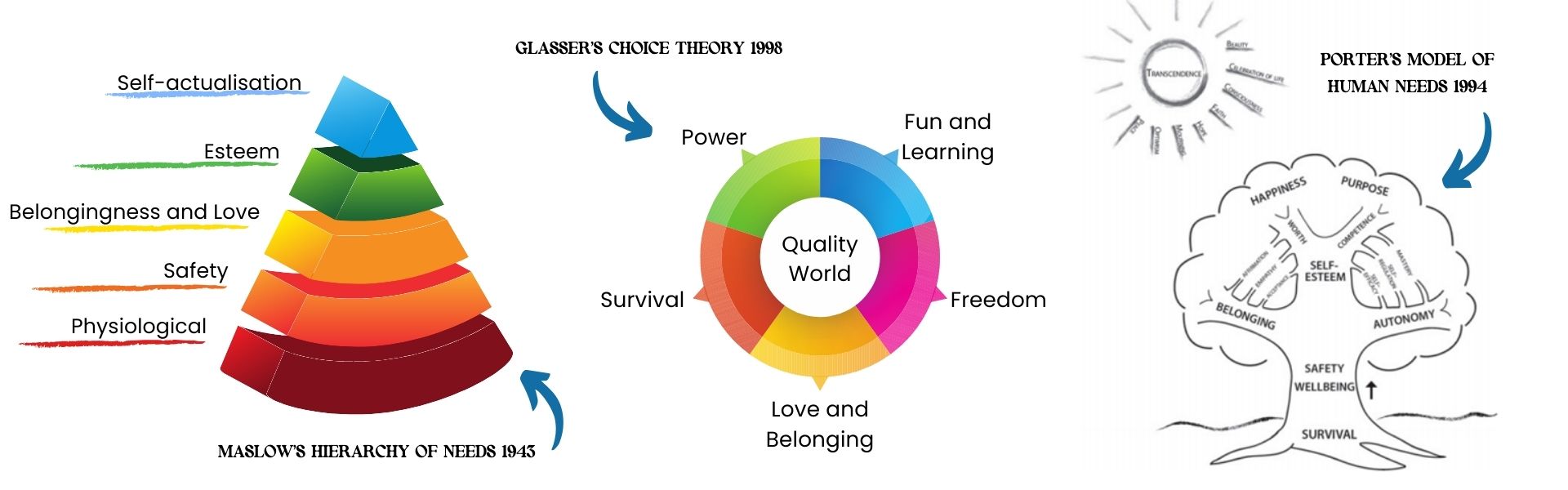

The needs proposed by the Phoenix Cups framework have been chosen based on evidence emerging throughout the 21st century about which needs are most important and which needs drive human behaviour via the a Will to Fill, or the will to meet the need (Friedrich Nietzsche, 1901; Schopenhauer, 1819). Maslow (1943), posed a widely accepted theory of human motivation, assuming that all behaviour is motivated to meet Physiological needs then Safety needs (illustrated by the Safety Cup in the Phoenix Cups framework), then Belongingness and Love needs (illustrated by the Connection Cup), then Esteem needs (illustrated by the Mastery Cup and the Freedom Cup), and to Self-actualise (illustrated by the ‘Skill to Fill’™ all Cups). Dr William Glasser (1998), proposed five basic human life needs that drive all human behaviour; Survival (illustrated by the Safety Cup), Love (illustrated by the Connection Cup), Freedom (illustrated by the Freedom Cup), Power (illustrated by the Mastery Cup), and Fun (illustrated by the Fun Cup). What was interestingly novel about Glasser’s Choice theory was the assumption that rather than a common hierarchy of needs, humans all have individual, genetically inherited, needs strengths profiles, with some people having a stronger need for Love (for example), while others might have a stronger need strength for Freedom. This needs strengths profile is illustrated in the Phoenix Cups framework by the notion of a unique ‘Cups profile’ whereby one person might have a bigger Connection Cup, while another might have a dominant (large) Freedom Cup. Other ideas influencing the Phoenix Cups framework include work from the Guidance approach (Gartrell, 2004; Hoffman, 1990; Kohn, 2006; Porter, 1999, 2014), and Dr Louise Porter’s (2008) comprehensive model of human needs symbolised as a tree with the trunk representing Safety and Survival needs, then Self-esteem, and branches representing Belonging, Worth, Competence, and Autonomy.

Finally, the emerging field of Positive Psychology is providing further fodder for this theoretical model, namely the findings of Ryan and Deci (2000) who postulate three innate psychological needs. These needs include Competence (illustrated by the Mastery Cup in the Phoenix Cups framework), Autonomy (illustrated by the Freedom Cup), and Relatedness (illustrated by the Connection Cup), which when satisfied yield enhanced self-motivation and mental health, and when thwarted lead to diminished motivation and wellbeing.

With this plethora of research, evidence, and literature, the shared language of the Phoenix Cups communicates a practical, visual, and simple to grasp framework. This approach is successfully being utilised to understand children’s behaviour and foster wellbeing in education and care services around the world.

In reflection, what an exciting twenty-three years it has been since that first lecture I attended. We are living in a time where the noble ideas of humanistic psychology, and philosophers of antiquity, are being rigorously studied and have hence found themselves moving from philosophical ideas to robust science. From the announcement of Positive Psychology to its natural evolution into Positive Education, there is plenty of evidence that it is now time for educational institutions to push children’s wellbeing to the forefront of their mission. Just as Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi (2000) called upon Americans to stop ignoring the human needs of its people, I ask teachers, educators, carers, and parents around the world to join me in thinking deeply about the human needs of our youngest citizens, and how we can design educational settings, from the early years up, that fill children’s Cups, not empty them, and foster children’s flourishing.

References:

Carlson, N. R., & Buskist, W. (1996). Psychology: The Science of Behavior (5th Edition ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Friedrich Nietzsche. (1901). The Will to Power.

Gartrell, D. (2004). The power of guidance. Delmar, Cengage Learning.

Glasser, W. (1998). Choice theory (1st ed.). Harper Perennial.

Hoffman, M. L. (1990). Empathy and justice motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 14(2), 151-172. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991641

Kohn, A. (2006). Beyond Discipline (10th anniversary ed.). Association for supervision and curriculum development.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Wilder Publications Inc.

Phoenix, S. & Phoenix, C. (2019). The Phoenix Cups: A Cup filling story. Phoenix Support Publishing.

Phoenix, S. (2022). Educator Toolkit for Behaviour. Wellington Point: Phoenix Support Publishing.

Porter, L. (1999). Behaviour management practices in child care centres. University of South Australia.

Porter, L. (2008). Young Children's Behaviour (1st ed.). MacLennan & Petty.

Porter, L. (2014). A comprehensive guide to classroom management. Allen & Unwin.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. Am Psychol, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

Schopenhauer, A. (1819). The World as Will and Representation.

Seligman, M., Ernst, R., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293-311. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27784563

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. Am Psychol, 55(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5